Sunday I listened to poetry. And I was reminded of the benefit of slow content. Particularly when it comes to learning.

We know the benefits of slow food. But the idea of slow content hasn’t caught on yet—though today’s hyperconnected, always-on, content-marketed-to-its-teeth world world is ripe for it.

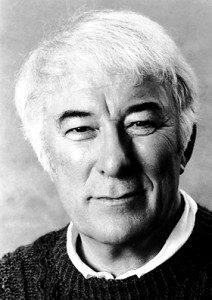

For a few hours Sunday I got a reprieve from the usual onslaught of information overload. I was at the Nâzım Hikmet Poetry Festival, which celebrates the work of the great Turkish poet and features another world poet each year. This year the festival highlighted the Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney, who died last August.

Poetry is the original slow content. Meant to engage the reader or listener, meant be read and re-read, to be understood and to mystify.

Isn’t that what you want for your content? Maybe not the mystify part, but the rest—for it to engage people, for them to want to go back to it again, to try to internalize and understand it in all its complexities.

Gibbons Ruark, the final poet to read at the festival, mentioned that the Irish folk musician Tommy Makem would sometimes read Heaney’s poem “Requiem for the Croppies” when he played. But Makem would change a word in the last line—”but” became “and.” And that small shift changes the poem, Ruark believes (and I agree), from elegaic to political.

That kind of distinction—and discussion—is possible with slow content, when you know Heaney weighed each word in his sonnet, when Ruark takes the time to be a slow reader, to learn from what Heaney did.

Requiem for the Croppies

by Seamus Heaney

The pockets of our greatcoats full of barley…

No kitchens on the run, no striking camp…

We moved quick and sudden in our own country.

The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp.

A people hardly marching… on the hike…

We found new tactics happening each day:

We’d cut through reins and rider with the pike

And stampede cattle into infantry,

Then retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown.

Until… on Vinegar Hill… the final conclave.

Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon.

The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.

They buried us without shroud or coffin

And in August… the barley grew up out of our grave.

Irish rebels during the period of the 1798 rebellion often wore closely cropped hair, a style associated with the anti-wig, anti-aristocrat French revolutionaries of the time, and were therefore nicknamed “croppies.” Heaney wrote his poem in 1966, 50 years after the Easter Uprising of 1916, but traces the roots of the 1916 events back to the 1798 rebellion.

Heaney, living where and when he did, was criticized at times for not being more political. He knew how, even in a poem about rebellion, to avoid the potential divisiveness of politics and create the inclusiveness of elegy.

In what ways, large or small, can you slow down your content? In honor of National Poetry Month, give it a thought.

Maybe reading a poem or two or three will help.

Celisa

P.S. Have you picked your poem for next Thursday?

Leave a Reply