In my previous post in this series I discussed differentiation as a key factor in pricing educational products. The basic idea was that it is difficult to set and get the prices you want if your product is not perceived as substantially different from the other options available to your customers.

In this post, I’ll take a look at price variation, the practice of varying the effective price of your offerings based on factors that come into play during the purchase cycle.

Variation recognizes that the value perception of your products changes from customer to customer, from time to time, and according to the context in which a purchase is made. By varying prices effectively, you can strike a balance between a customer’s price sensitivity and the level of value you deliver.

In short: you provide options. Doing this ensures that you will attract as many customers as possible at the maximum price point for each customer.

Establishing and Managing Your Value Continuum

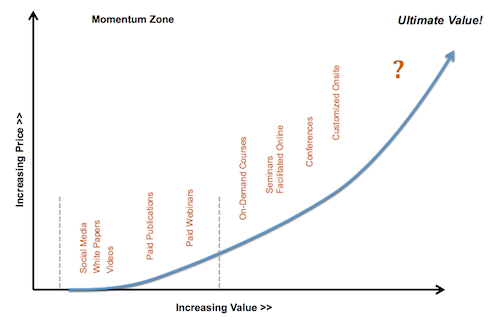

The first step in managing price variation is to understand how value changes across your portfolio of products. We use what call the Value Ramp as a simple but powerful tool for visualizing the “value continuum” your organization offers.

The curve – which places lower priced (including free), lower value offerings at the bottom left and the highest priced, highest value offerings at the upper – forces you to draw an explicit price-value relationship and it exposes very effectively whether there are any value gaps. Simply drawing this curve on a white board and engaging in some discussion around it with your staff, board, and/or volunteers can be a very enlightening exercise.

The most essential step in managing price variation is to ensure that you are offering options all along the curve, thus ensuring that there are ways prospects who need to get a better sense of your value can engage with you easily and at low cost (in the lower half of the curve). Similarly, those who already value your offering highly have options for accessing as much value as possible (in the upper half of the curve).

Establishing this sort of value continuum does not mean that you have to develop completely different products to fill in the points along the curve. Fortunately, there are good strategies for adjusting value – and price – without having to change the core of your offering. Let’s take a look at the three most common ones.

Strategies for Varying Price

There are three major strategies for varying price across your value continuum:

1. Discounting and bonuses

Discounts and bonuses shift the curve up or down. Value stays the same, but price decreases; or, value increases, but price remains the same.

While discounting tends to be the more common approach used by organizations, I strongly prefer bonuses to the extent that this strategy is used at all. Psychologically, a bonus feels more like a “gift” to the purchaser, and done correctly, bonuses can be used to expose purchasers to levels of value they had not been aware of previously.

Discounts, unless done very judiciously, have a tendency to erode value perception, and they can have much more of an impact on margins that organizations tend to realize: an X% reduction in price can easily require a 2X% increase in volume to maintain the same margins.

Whichever you pursue, be sure you have a good reason for discounting or bonuses. The goal always is to reward desirable behavior. Reasons might include:

- To reward loyalty (e.g., high volume purchases, purchase of multiple products, repeat/long-term customers)

- To penetrate a new market or market segment (But be careful to set and communicate clear parameters.)

- To gain additional customers from organizational customers (e.g., two people participate, get 3rd for free)

- To move current customers into additional offerings (e.g., because you liked x, we think you will like y, here’s a discount to give it a try)

- To reduce risk (e.g., early bird rates for conferences)

- To grab market share from competitors (Be very careful with this one: you need to be sure that demand for your product is elastic – i.e., that a drop in price will drive a significant increase in volume. You also want to avoid starting a price war.)

- To get valuable information (i.e., tell us about your current challenges and we’ll give you a discount on X)

2. Bundling and Unbundling

While discounting and bonuses move the curve up or down, bundling and unbundling are strategies that move offerings higher or lower on the curve by adding or subtracting value.

It is important to grasp that doing this effectively requires designing and developing products with this strategy in mind. For example, I often see courses from which individual lessons or segments could – in theory – easily be sold. Unfortunately – in practice – the courses have been created in such a way that the lessons simply don’t stand effectively on their own. Turning them into distinct products would require significant work.

In most cases, bundling is going to most effective when used in conjunction with a relatively high-value, flagship product to which high-margin complementary products can easily be added. The classic example, of course, is the “value meal” at fast food restaurants. The flagship product might be a Big Mac, for example. Adding fries and a drink – both of which are very high margin items – increases the value for the purchaser while also generating significant additional net revenue for the restaurant. In the world of education, you might bundle a set of publications and a Webinar series together with a place-based seminar or conference to create an offering that shifts towards the upper right of your Value Ramp.

With bundling, you, the seller, make the choices about what goes into the package and then assign value based on your understanding of what the customer may be willing to pay. Unbundling, on the other hand, shifts choice to the customer, and makes it possible for the customer to move herself higher or lower on the curve based on what she value.

For example, you might break the pieces of a certificate program into individual offerings to attract customers who do not really want the entire program. Each individual piece would generally be priced a good bit higher than if it were packaged into the full program. Or, you may put the choice to add value into the hands of the customer. You may, for example, make it the customer’s choice to add the publications and Webinar series to the seminar or conference referenced above.

One word of caution: unbundling can be highly disruptive. Many are pointing to the rise of MOOCs, for example, as effectively unbundling the university and potentially damaging the entire market for higher education. Similarly, Apple’s introduction of iTunes, which unbundled the traditional album by offering easy access to singles for 99 cents, had a significant negative impact on music industry revenues. But Apple, of course, had other strategic fish to fry: iTunes was a the major factor in driving sales of Apple’s iPod and it effectively transformed Apple into a major media company.

If you are seeking to transform not just your pricing, but also you entire business model and industry, unbundling may offer some interesting options.

3. Customization

Customization goes beyond merely adding or removing features – an approach covered by bundling and unbundling – to modifying a product or service to fit the needs of a specific customer. In terms of the Value Ramp, it is the most relationship-driven approach to increasing the value of a product or service. As such, it also commands the highest price out of the offerings along your value continuum.

An example might be adapting a classroom-based seminar for delivery as onsite training at a specific company. The seminar might be altered to include case studies drawn from the company itself or its market, and it might be supplemented by some primary research – e.g., a survey, interviews – to help illustrate critical points or spark discussion.

While customization, by its nature, cannot be automated and scaled to quite the same degree as other approaches to variable pricing, that does not mean there is no possibility for automation or scale. The use of templates, tested methodologies, and other standardized approaches, for example, can make customization much easier. In the example above, a standard template might be re-used from client-to-client for conducting a survey. It is the analysis of the surge and incorporation of the data into the seminar that represents the customization – and the real value.

In general, I find that most organizations do little, if anything, in this area of their value continuum, and as a result, do not position themselves to offer higher priced, high margin offerings. As a result, significant amount of potential business is simply “left on the table.”

Differentiation + Variation = Optimization

To wrap up, the core message of this two-part series is that if you are able to differentiate your offerings as much as possible from other options and then provide those offerings at a variety of price-value levels, you will strike a balance between sales volume and price that maximizes your net margins.

Even for nonprofit organizations, achieving this sort of price optimization is nothing to shrug at: net margins can be reinvested in the organization to fund new initiatives or to support programs that are unlikely to ever be profitable.

One final, important note: optimization is an ideal. It is something to strive for, but really it is difficult, if not impossible, ever to be certain you have achieved it. No organization has perfect market knowledge, and even if it did, circumstances change too rapidly for that knowledge to remain perfect for long. Nonetheless, continual efforts to differentiate your offerings and provide a variety of price-value options are certain to improve the overall performance of your education business.

Jeff

See also:

Leave a Reply