The learning experiences we offer are the essence of our learning businesses, and to design, develop, and deliver meaningful, effective learning experiences, we need to understand the adult learning principles embodied in andragogy.

In this guide we’ll define what andragogy is, look at the six guiding principles of andragogy, and explore how learning businesses can apply those principles to the learning experiences they offer.

Read on for what you need to know, or you can download a PDF of this guide by clicking the button below. In addition to being useful on its own, we also recommend the guide as a resource for the Portfolio domain of the Learning Business Maturity Model.

Andragogy Definition: What Is Andragogy?

First, let’s establish an andragogy definition. To discuss what andragogy is, is to discuss who Malcolm Knowles is. Knowles (1913-1997) is often called the father of andragogy, though the term andragogy pre-dates him, coined in 1833 by Alexander Kapp, a German educator, to distinguish the study of adult learning from pedagogy, which deals with teaching children. Whatever the term’s origin, Knowles is inarguably andragogy’s poster boy.

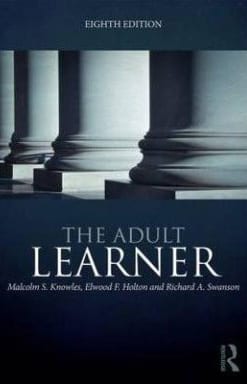

In 1973, Knowles publishes The Adult Learner, a classic in the field of andragogy and one with staying power—the book outlives Knowles and has been updated and re-released periodically (it’s currently in its eighth edition). The Adult Learner outlines key assumptions, or principles, about how and why adults learn. The have become the core of what we understand adult learning principles to be.

Which, of course, begs the question, Who is an adult? Knowles adult learning theory relies on a psychological definition: “Psychologically, we become adults when we arrive at a self-concept of being responsible for our own lives, of being self-directing…. [M]ost of us probably do not have full-fledged self-concepts and self-directedness until we leave school or college, get a full-time job, marry, and start a family.” (64)

His list of adult characteristics feels a bit anachronistic when debate about the value of a college education is driving alternative credentials, the gig economy is in full swing, and adults are staying single longer, but his larger point—that self-concept and self-directedness are the defining criteria of adulthood—still works well today (even if I find it hard to claim my self-concept is “full-fledged” though I’ve left college, am married, and have a full-time job and kids).

The Six Guiding Principles of Andragogy

Knowles’s andragogical model is grounded in six adult learning principles (which he, good scientist, called assumptions):

- The need to know

Adults need to know why they need to learn something. - The learners’ self-concept

Adult learners expect to be responsible for their own decisions. - The role of the learners’ experiences

What adult learners know and have done already impacts how they learn. - Readiness to learn

Adults become ready to learn when they need to know or do something in their life. - Orientation to learning

Adult learners are life-centered (or task- or problem-centered) rather than subject-centered. - Motivation

Internal motivators are more effective than external ones.

Knowles posits only four assumptions in the first edition of The Adult Learner. The assumptions about motivation to learn (#6 above) and the need to know (#3 above) are added in subsequent editions.

We can use these six principles to guide our design, development, and delivery of learning products and services for adult learners. We’ll examine them in order, with an emphasis on how each applies to the learning experiences we provide. (You can also jump to a specific section of the guide using the links in the list of principles above.)

The Need to Know: Adult Learners Need to Know Why

Knowles writes, “Adults need to know why they need to learn something before undertaking to learn it.” (64) You might have heard this principle phrased as “What’s in it for me?” or simply WIIFM.

This assumption seems obvious, but too often (at least in my experience) this principle is skipped over or only partially embraced. Letting this principle guide you means beginning with your marketing—not your promotion only, but a marketing approach that encompasses all four Ps. Embracing this principle begins with doing the tracking, listening, and asking necessary to understand what your learners need to know. If you do your homework to discover the learners’ needs upfront, then the learning experiences you create will be grounded in this first principle that adult learners need to know why they need to learn whatever the topic is.

You also need to communicate the why to the learners, and you need to build in opportunities for them to explore and make the why as personal as possible. As you design and develop a learning experience and promotions for it, you want to ask:

- What are the outcomes learners will be able to achieve based on this learning experience?

- What positive change will you help them create?

Then communicate those answers to the learners.

As you deliver a learning experience, overtly tie the content or skills you’re teaching back to the outcomes and positive change the learners are after. Even more importantly, help learners make such connections for themselves. They’re better able than you are to make the why of any learning experience more meaningful and specific. You just need to encourage them and give them the cognitive space to do so.

Such encouragement and cognitive space might take the shape of simple reflection questions—e.g., “What are your biggest challenges with pricing?” or “Which of the tactics just covered would help you most in generating ideas for new educational products?”—along with some quiet time to think and jot down notes or an opportunity to share in pairs or small groups. Or you might scaffold the experience with real-world examples or more formal case studies that show how a concept has played out for an individual or organization.

Reflection Question: Have you identified the underlying whys that might bring learners to each of your products and services?

Self-Concept: Adult Learners Expect to Be Responsible

In The Adult Learner, Knowles explains this second of the adult learning principles of andragogy as follows:

Adults have a self-concept of being responsible for their own decisions, for their own lives…. They resent and resist situations in which they feel others are imposing their wills on them. This presents a serious problem in adult education: The minute adults walk into an activity labeled “education,” “training,” or anything synonymous, they hark back to their conditioning in their previous school experience, put on their dunce hats of dependency, fold their arms, sit back, and say, “teach me.” (65)

“Dunce hats of dependency.” What a wonderful—if completely undesirable—image. Knowles points to a huge problem we face as learning businesses—sometimes our learners are hostile. Expecting to be treated as dependents, they sit and wait to be spoon-fed. Based on their earlier K12 education, many adult learners don’t expect to be asked to be full participants in learning experiences. This has at two least implications.

First, adult learners don’t necessarily come to learning experiences knowing how to be active, self-directed learners. Two years after The Adult Learner first comes out, Knowles publishes Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers, a practical primer, to help fill that knowledge gap.

Second, learner engagement can be abysmally low among adults. Which is why we see so much attention on engagement and engagement tactics and fervent discussions of how we get learners to stop sitting back with folded arms and start leaning forward and sharing their questions, insights, and experiences.

To address these two points when we design, develop, and deliver our learning experiences, choice becomes critical. Being responsible implies making choices. Offer options in how learners can engage with your content. That may mean offering the same content in different formats (e.g., having an audio, video, and text options for each major point in a learning experience). It may mean offering different ways of interacting with the content (e.g., offering a self-paced course and a synchronous course). It may mean providing additional resources and readings or an online community or listserves so the learners can decide how deep (or shallow) to go on a topic. And/or it may mean something else. Actively think about what choices you can provide—and then provide them.

Above and beyond what you can do for a slice of content or a particular course, you might also choose to look at overarching resources that will support your customers becoming effective self-directed learners. At the less scaffolded end of the spectrum, you might point them to resources (like Self-Directed Learning or 10 Ways to Be a Better Learner). At the highly scaffolded end, you might create a service to help learners identify their personal needs and then create an individual learning plan.

The more your learners are able to connect their own answer to “Why learn this?” to the learning experience, the more they’ll value the experience. In that sense, self-directed learning ties to the work of behavioral economist Dan Ariely, who described the phenomenon that “labor enhances affection for its results” as the “IKEA effect.” IKEA sells a lot of some-assembly-required products—and has been very successful at it.

IKEA, Ariely, and Knowles all get at the same principle—we value what we have a hand in, what we’re responsible for. Whether that’s a bookshelf I assembled myself one sunny afternoon or the creative writing workshop where I realized Tony Hoagland’s five powers of poetry has some application to learning businesses.

Reflection Question: How do you (unintentionally) invite your learners to “put on their dunce hats of dependency”? How might you encourage and support learner responsibility?

Experience: What Adult Learners Know Already Impacts How They Learn

Learners of all ages bring their past experience to any situation, and that past experience determines what and how they learn. Adults, simply by virtue of being older than children, bring more years of experience.

But it’s not only a question of quantity of experience increasing with age. Variance increases too. Standards in the US public school system exist to ensure (at least in theory) that a fourth grader in one school and a fourth grader in another school both will complete the school year with a common set of skills and knowledge. With adult learners, it’s much harder to know what skills and knowledge will be mutual: “Any group of adults will be more heterogenous in terms of background, learning style, motivation, needs, interests, and goals than is true of a group of youths.” (66)

This issue of prior knowledge poses both a problem and an opportunity. The problem is we as providers of learning have to do the work to make sure we position learning experiences appropriately, so adult learners know which of our offerings might be a fit for them. It might mean labeling offerings as intended for novices, those with intermediate knowledge and skills in the topic, or experts. It might mean making use of pre-assessments and prerequisites. It might mean assigning pre-work so all learners come to a learning experience with some shared baseline knowledge.

And then once learners are engaged in a learning experience (having hopefully picked one appropriate for their prior knowledge), we should work to draw out the learners’ experience and expertise:

[F]or any kind of learning, the richest resources for learning reside in the adult learners themselves. Hence, the emphasis in adult education is on experiential techniques—techniques that tap into the experience of the learners, such as group discussions, simulation exercises, problem solving activities, case methods, and laboratory methods instead of transmittal techniques. Also, great emphasis is placed on peer-helping activities. (66)

Knowles offers a list of techniques and tactics we can use to draw out the experience our adult learners bring. Time for reflection, discussion questions, case- and problem-based activities, simulations, and hands-on practice all can elicit learners’ prior knowledge. Sometimes we as learning businesses can get too caught up in the desire to look like we have all the answers, even if we don’t. That’s a mistake to avoid. Don’t be afraid to acknowledge the expertise resident in your learners. Give them opportunities to share their experiences and to draw on these experiences as they engage in your products and services.

Peer learning offers the potential for one learner’s experience to directly help another learner. And there’s the potential for a learner’s experiences to help her learn better, through elaboration, one of the learning strategies showcased in Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Relating material to what you know already is a common approach to elaboration.

So drawing on our learners’ experiences represents a great opportunity. And not drawing on them presents a danger. As Knowles puts it, “To children, experience is something that happens to them; to adults, experience is who they are. The implication of this fact for adult education is that in any situation in which the participants’ experiences are ignored or devalued, adults will perceive this as rejecting not only their experience, but rejecting themselves as persons.” (67)

And there’s a second danger inherent in prior knowledge. Even when we as learning providers acknowledge and draw it out, prior experience can bring the curse of knowledge, biases, or inappropriate expectations. There too we have work to do in positioning our offerings and in delivering them in ways that seek to surface and address such unconscious tendencies. Indeed, our most important work with adult learners may sometimes be helping them unlearn.

Reflection Question: What techniques and tactics do you use to draw out learner experience and expertise? What additional approaches might you employ?

Readiness to Learn: Adults Become Ready to Learn When They Need

Knowles summarizes this principle of andragogy as, “Adults become ready to learn those things they need to know and be able to do in order to cope effectively with their real-life situations.” (67) I’ll summarize it even more briefly: relevance.

Adults tend to be most interested in learning what has immediate relevance to their lives. Adults prefer learning things they can actually use, preferably ASAP. So we need to provide exercises and activities that prompt learners to tie what they’re learning back to their own lives and work. And, where possible, we should provide bridges that encourage that tie-back and application: checklists, worksheets, and other tools learners can use in the context of their lives and work.

One caveat (admittedly a caveat that comes from a liberal-arts grad): We needn’t go so far as to assume all learning must be practical and for immediate use. Adults also want to learn things that support and enhance their self-image—they might want to be seen as someone who appreciates Walt Whitman and Mary Oliver or who can tell a Barolo from a Beaujolais or even be “certified” to do whatever they do. While achieving these ends may involve concrete skills and knowledge, much of the relevant value is emotional or psychological. Even more shockingly, there are still the learners who believe in learning for the sake of learning. We can serve them too.

Reflection Question: What approaches do you use to ensure learners begin to apply what they’re learning to their life and work as immediately as possible?

Orientation: Adult Learners Are Life-Centered

This principle dovetails with the readiness-to-learn principle just discussed. Knowles asserts, “Adults are motivated to learn to the extent that they perceive that learning will help them perform tasks or deal with problems that they confront in their life.” (67) And so adult learners tend to be life-centered (or task-centered, or problem-centered) rather than subject- or content-centered.

Once we have adult responsibilities (think back to Knowles’s list: full-time job, kids, etc.), most of us have limited interest in knowing stuff just for the sake of knowing stuff—or at least we have limited time to spend learning such stuff.

As a result, most adults don’t want information from a learning experience—they may already be drowning in too much information. What they want is meaning. This is one of the reasons the case study method is so popular in business schools like Harvard’s. Give your learners case studies. Give them activities and assignments that enable them to apply their new knowledge in the context of their own lives. Approaches like these help learners move beyond content and into the application of learning to life.

Identify and emphasize the problems and tasks from real life your offerings help learners with. Focus your promotion on those tasks and problems—use them in the subject line of your e-mail marketing. Maybe even rethink how you name products and services –not subject-centered “Andragogy 101” but task-centered “How Andragogy Can Help You Develop Better Courses.”

Reflection Question: How topic- or subject-centered are your learning offerings and your promotion of them? How might you restructure or reposition what you offer to highlight the real-world problems and opportunities they address?

Motivation: Internal Motivators Are More Effective

“Adults are responsive to some external motivators (better jobs, promotions, higher salaries, and the like),” Knowles writes, “but the most potent motivators are internal pressures (the desire for increased job satisfaction, self-esteem, quality of life, and the like).” (68) This means we as learning businesses should support learners’ internal motivation—but how can we intrinsically motivate others?

For ideas on how to undertake that quixotic task (and for a deeper understanding of motivation in general), Edward Deci’s Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation is an excellent resource. One of Deci’s most interesting findings is that extrinsic motivation isn’t simply less effective than intrinsic motivation; extrinsic motivation can erode intrinsic motivation. So we have to be careful about how we use extrinsic motivators—whether praise, a digital badge, or even a certification designation—and build in support for learner autonomy and intrinsic motivation.

We have an opportunity to leverage motivation at three key points:

- When a decision is made to engage in a learning experience (e.g., the decision to buy a course, register for a conference, or devote time to self-study)

Here motivation impacts whether individuals decide to learn, what they decide to learn, and which option they choose from an array of possibilities. - During the learning experience itself

Here motivation determines how much attention the learners give to the experience, how invested they are in understanding what’s being taught, and in engaging wholeheartedly in the activities. - Applying the learning

Here motivation impacts how well what’s been learned will be applied on the job, in the real world—or whether that learning will be applied at all.

The more choices and decisions at each of those three points—the decision to engage in learning, the participation in a learning experience, and the application of the learning—the more we as learning businesses can create conditions that foster intrinsic motivation. And when learners are more internally motivated, the more effective the learning and therefore the greater the impact.

That said, too much choice can be problematic (think information overload and analysis paralysis), so we need to set context, curate, and frame things in ways that give learners choices but are rational and relevant.

Reflection Question: What extrinsic motivation do you tap? How might you emphasize the intrinsic value of your learning offerings?

Andragogy: From Theory to Practice

In all likelihood, you not only hope your learners leave your learning experiences with new knowledge and skills but that they apply those new skills and knowledge. You want them to use what they learn to change how they act and to achieve positive outcomes.

With your new (or renewed) understanding of andragogy, our hope is the same: application and—as a result of application—impact. Helpful as an understanding of andragogy may be, andragogy’s real benefit will only be apparent when you delve into how the six guiding principles can inform and change how you design, develop, and deliver learning experiences.

You probably won’t (probably shouldn’t) change your approaches wholesale. But it can be helpful to use the adult learning principles embodied in andragogy as the basis for an audit of your current learning portfolio.

- Which of the six adult learning principles do you tend to support?

- Which principles are you weak on?

Perhaps you’re strong across the board about making the WIIFM clear but tend to be subject-centered. Or maybe a particular product line—say, your instructor-led, day-long workshops—is well grounded in the principles, but another—say, your Webinars—is developed without anyone actively attending to the principles.

Once you understand where your portfolio is generally, you can begin to make tweaks or bigger changes as part of your revision process. And, as you introduce new products and services, you can apply the theory.

Whenever possible, you want your learning experiences to support all six principles fully. But we are in the learning business after all, and there may be times when circumstances justify departures from the principles. Following an andragogical model takes time and effort, particularly until you and your team get used to translating the principles into particular approaches and practices, and so in the case of emerging topics or free or low-cost offerings, it may make sense to forego hitting on all six principles.

Even if you apply all six adult learning principles to a learning experience, that doesn’t ensure you’ll have a blockbuster product—but you will almost certainly have a much better product than you would have had otherwise and have a product capable of supporting you in your drive for improving the impact of your learning experiences on the learners, their profession or field, and society at large.

Celisa

Works Cited

Knowles, Malcolm Shepherd, Elwood F. Holton, and Richard A. Swanson. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 2005. Unless otherwise noted, the quotations above come from this book.

Brown, Peter C., Mark A. McDaniel, and Henry L. III Roediger. Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Reading & Listening List

The following list collects the works cited as well as the other books, articles, podcast episodes, and other resources mentioned in this article, in the order in which they appear.

- The Adult Learner [book]

- “The 4 Ps of Marketing Your Learning Business” [podcast episode]

- “The Market Insight Matrix Can Help You Build the Right Learning Products” [blog post and resource]

- “Andragogy—the Rub” [blog post]

- Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers [book]

- “Learner Engagement—What It Is and How to Foster It” [podcast episode]

- 10 Ways to Be a Better Learner [book]

- “HBR Breakthrough Ideas for 2009” [blog post]

- “Learning What Is Untaught” [blog post]

- “Emphatically Recommended Readings” [blog post]

- Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning [book]

- “Getting Conscious About Bias with Howard Ross and Shilpa Alimchandani” [podcast episode]

- Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation [book]

- “Exploring Motivation and Learning” [podcast episode]

- “Capitalizing on Curation” [podcast episode]

- “One Word: Impact” [podcast episode]

Online Learning and the Future of Education with Ray Schroeder

Online Learning and the Future of Education with Ray Schroeder

Leave a Reply