While arguably lifelong learning has always been a vital part of human existence, it’s hard not to notice the new level of emphasis that has been placed on it in recent years.

In 2017, The Economist declared lifelong learning an “economic imperative,” and it has hardly been the only publication in mainstream and business presses to insist on the importance of learning in a world where the scale, scope, and speed of change seem much higher than ever before.

As The Economist’s interest in the topic suggests, much of the concern over lifelong learning ties back to the employment market and to business productivity and growth. Terms like “upskilling” and “reskilling” have become trendy ways to describe what workers must do—or have done to them—if they expect to remain relevant and remain employed in the current economy.

But, while much of the focus has been on formal education and training tied to employment, the demand and supply for lifelong learning are much broader. From YouTube videos to social media communities to the age-old institution of local book groups, lifelong learning permeates nearly all aspects of our lives whether we are conscious of it or not—and technology has multiplied the options exponentially.

Information may want to be free, as some have suggested, and knowledge may be invaluable, but it became clear long ago that there is money to be made from all this learning activity. People will pay, sometimes handsomely, for access to content and experiences that promise to improve their condition. As a result, there is a thriving and growing global market for lifelong learning.

In this article, we’ll look at key aspects of this market and consider how it is likely to evolve in coming years.

Defining Lifelong Learning

As with so many things in life, what “counts” as lifelong learning is often skewed by the perspective of the person talking about it or the group seeking to serve lifelong learners. So it’s important to understand our perspective, which informs all that is written in this piece..

Our view at Leading Learning is that lifelong learning, by definition, occurs throughout life. It is not limited to adulthood or late adulthood. That said, in our own work we have chosen to focus specifically on adult lifelong learning, and the focus of the article is on the market for adult lifelong learning.

We also believe it is important to recognize that lifelong learning is not limited to education and training or to formal activities. “Learning” is much broader than “education” or “training,” and it occurs, as UNESCO puts it, in “life-wide contexts (family, school, the community, the workplace, and so on) and through a variety of modalities (formal, non-formal and informal).” It also applies not just to skills or knowledge but also to behaviors and attitudes—the latter two being particularly important in how we make sense of the world and participate in it as responsible citizens.

Finally, while many definitions of lifelong learning stress consciousness and intentionality on the part of the learner (see this definition from Eurostat, for example), we believe it’s important to recognize that learning occurs across a spectrum of consciousness and intentionality. People can and do learn without necessarily being aware of the fact they are learning or having any conscious intention to learn. Arguably, most learning happens that way.

As we’ll see, these distinctions matter when considering the potential opportunities in the market for lifelong learning. The market is considerably larger and—in our view, richer—when it is seen to include both formal and informal as well as intentional and non-intentional learning.

In the end, we don’t really distinguish lifelong learning from learning itself. “Lifelong” simply emphasizes that learning is ever-present in the life of every human being. So, to succinctly define “lifelong learning,” we rely on the definition of learning we’ve offered on Mission to Learn:

Learning is the lifelong process, both conscious and unconscious, of transforming information and experience into knowledge, skills, behaviors, and attitudes.

How Big Is the Adult Lifelong Learning Market?

It’s very hard to say how large the total market for lifelong learning is, mostly because of the limited definitions of “lifelong learning” and “adult learning” that most market analysts use. We do, however, have significant clues.

In a pre-pandemic article, Forbes reported that the adult learning services market in the United States, both online and offline, was about USD 10 billion as of 2016. Forbes also estimated the market size—the number of people who would be new consumers of adult education—at around 32 million adults.

Aside from being U.S.-centric, the Forbes article focused specifically on “the market for helping adults learn basic skills or develop workforce skills” and draws on data from companies that serve that market. It was also published before COVID-19 pushed the world online, resulting in a boom in e-learning, and before ChatGPT changed the playing field for digital content creation, delivery, and consumption.

Roll forward to 2023, and some sources project the size of the U.S. continuing education market as USD 93.25 billion by 2028, with generative AI being a major driver of growth. Other sources have valued the global continuing education market at USD 33.55 billion in 2022 and project it to grow to around USD 58 billion by 2030.

Again, definitions are a big issue. The analysts and reporters behind the estimates cited here are loose with their language—adult learning, adult education, continuing education—and with the underlying meaning of the terms. Yet clearly something big is going on—and growing.

Perhaps by necessity, analysts tend to focus on products and services that are relatively well defined and measurable. The reports we link to rely on numbers from companies and institutions that are clearly in the education and training space. But there is a much larger portion of the adult learning market that does not typically get accounted for.

The global meetings market has been estimated at USD 1.2 trillion. Arguably, nearly every meeting contained in this estimate is a source of learning, whether formal or informal, for the participants. Trade and professional associations, for example, routinely provide extensive continuing and professional development opportunities as part of their annual meetings—and that’s just the formal aspect of the learning that goes on.

The global content marketing industry was estimated at USD 63 billion in 2022. While it would likely be impossible to determine the exact percentage, a significant portion of this activity is educational—again, both formal and informal—in nature. While, by its nature, content marketing may not produce revenue directly, it is a huge indirect driver of revenue for the companies and individuals that produce it.

And none of the figures cited so far take into account the burgeoning industry of edupreneurs—people who are part of the broader creator economy and generate significant revenue through blogging, live streaming, creating online courses, membership sites, and other offerings aimed at monetizing their expertise and helping their followers and customers learn.

As an example, Teachable, one of the major online course platforms, claims more than 100,000 creators who have earned more than USD 500 million to date through courses and coaching. Teachable is just one of many similar companies. Goldman Sachs projects the broader creator economy will be valued at USD 480 billion by 2027.

The list could go on.

The point is that opportunities for learning and growth are everywhere, and the market for lifelong learning is much larger than is reflected in currently available analysts’ reports. For those seeking to serve the market, understanding this discrepancy may be the key to seeing opportunities that others don’t yet see.

Need Help Reaching Your Market?

At Tagoras, the parent company of Leading Learning, we are experts in the global market for continuing education, professional development, and lifelong learning. For more than two decades, we have helped a wide range of organizations increase the reach, revenue, and impact of their educational offerings.

Major Providers of Lifelong Learning

There are many ways in which lifelong learning can be delivered and supported, and, as a result, there is a wide range of organizations that might be categorized as lifelong learning providers. Among organizations intentionally and primarily focused on lifelong learning as a market, however, there are four major categories of providers: academic institutions, trade and professional associations, commercial learning providers, and edupreneurial expertise-based businesses.

Academic Institutions

Continuing education and “extension” education programs have been a part of college and university offerings for more than 150 years. The roots of Harvard University’s continuing and extension education, for example, can be traced to the Lowell Institute, founded in 1836. Cambridge University’s Institute of Continuing Education (ICE) dates back to 1873.

In more recent times, as debates have flared about the costs and value of traditional degree programs and the focus on lifelong learning has increased, academic continuing education units have gained more prominence. A report from Encoura points to that growth:

[N]on-degree program interest has grown from 34% in 2019 to 47% in 2022, a 38% increase over that time. This compares to a 3% increase for undergraduate programs and a 38% decrease among graduate programs. Amid debates about debt and return-on-investment, graduate prospects seem to be hedging toward faster and cheaper alternatives.

Increasingly, leaders of professional, continuing, and online education (PCO)—the phrase often used to identify contemporary continuing education programs—are seeing opportunities in addressing workforce development needs and providing alternative forms of credentialing to help adults navigate the modern career landscape. Indeed, pressure to reevaluate their core value proposition and business models has, in my estimation, put these providers well out ahead of their counterparts in the trade and professional association world in pursuing the issuance and management of standards-based digital credentials.

An advantage these organizations usually have is access to broader institutional infrastructure along with access to institutional faculty with subject matter expertise and teaching experience. Additionally, they may be able to capitalize on the brand—whether local, regional, national, or international—of the institution with which they are associated and automatically be seen as a trusted, authoritative source of learning.

In many instances, particularly at community colleges and lower-tier universities, continuing education offerings may be taught by actual practitioners in the subject matter covered. Of course, in other instances, academic lifelong learning programs may be subject to the sort of “ivory tower,” “out of touch with the real-world” criticisms commonly leveled at degree-focused programs. Additionally, decision-making, particularly when it comes to allowing credit to be granted for an offering, can be very slow in academia, which is a key reason why many PCO programs are turning more of their attention to non-credit programming.

Trade and Professional Associations

While academic continuing education arguably enjoys broader public awareness, trade and professional associations are likely the largest single source of organized lifelong learning for adults.

Because they can be organized in many ways, there is no truly reliable data on the number of these organizations. Even the American Society of Associations Executives (ASAE), the “association of associations,” provides estimates that range from roughly 67,000 to nearly 91,000. (By comparison, the National Center for Education Statistics reports 3,542 degree-granting postsecondary institutions in the U.S. as of the 2020-21 academic year.)

What is clear is that associations reach a lot of people, whether they are direct individual members or employees at the corporate members of trade associations. What is also clear is that most of these organizations provide education to their members formally, informally, or both, and most professional/individual membership associations specifically cite education as part of their mission and/or their strategic plan. They typically pursue this part of their mission through programming offered through their education departments and at myriad events that are part of the trillion-dollar meetings industry highlighted above.

While academic institutions have faced something of a crisis related to the cost and value of their degrees, associations have faced a crisis related to the value of membership. The general concern is that younger generations do not value traditional membership, and associations may be facing a significant decline in membership along with a corresponding decline in dues revenue.

Whether that concern becomes a reality may depend largely on the degree to which associations fully capitalize on their position as leaders of lifelong learning. Because associations tend to be member-driven, they are arguably in a much better position than academic organizations to identify and certify essential knowledge in the fields and industries they serve, to spot emerging trends, and to lead the way in addressing new learning needs. They also often have access to the best practitioners in the fields and industries they serve and can tap these people as subject matter experts and instructors.

One of the biggest downsides to association-driven lifelong learning is that these organizations have a strong tendency to be “all things to all people.” The drive to serve all parts of a member base can lead to taking on a higher volume of educational offerings than an organization can reasonably maintain while also ensuring high quality. Additionally, the teaching capabilities of the volunteer subject matter experts on which most associations rely can vary dramatically, and many association education staff end up in their positions by chance, with relatively little formal background in adult education and training.

Commercial Learning Providers

There have always been a range of companies serving the adult lifelong learning market with correspondence courses, seminars, distance learning, and e-learning, but the past decade or so represents a tipping point for “Big Learning.”

Udemy, an online course publishing platform and marketplace, was founded in 2010, and, according to the company’s Web site, has since grown to host more than 210,000 courses authored by more than 75,000 instructors. Coursera and edX, the two largest and most recognizable massive open online course (MOOC) providers, were both founded in 2012. Lynda.com, which was founded in 1995, was acquired by LinkedIn—and then rebranded as LinkedIn Learning—for a whopping USD 1.5 billion in 2015. That same year, The Great Courses, founded in 1990 as The Teaching Company, launched its online subscription service, Wondrium.

These are just a few of the bigger names in a large constellation of companies that see significant opportunity in providing learning experiences to adult lifelong learners. In some ways, the growth of these companies in the market has been a welcome disruptor. They have created competition where little to none existed before, often forcing academic and association providers to pay more attention to the relevancy and quality of their offerings as well as to related areas like customer service.

The drive to be competitive—combined, in many cases, with pressure from investors—often spurs commercial providers to focus more on innovation, particularly technological innovation, than academic and association providers. Arguably, digital badges have managed to gain traction mainly because the large MOOC providers and LinkedIn have found them valuable. And much of what is happening with artificial intelligence in education is being driven by companies like Duolingo and Khan Academy.

But what giveth also taketh away. The increase in supply and corresponding competition have led to the commoditization of education as a product in many instances. The resulting downward price pressure—often to the point of free—has made creating and sustaining viable business models difficult for many of the commercial disruptors as well as for the traditional providers they have disrupted. Stories of layoffs and cost-cutting are becoming common.

Moreover, what is most profitable from a business standpoint is not necessarily what is most effective from a learning perspective. It’s relatively easy to churn out a high volume of talking-head-and-PowerPoint-based video content, but the learning value of this content is often questionable. Defenders of MOOCs will say that the high dropout rates—greater than 90 percent according to various estimates —are a result of learners simply getting what they need for a course, then leaving. A better bet may be that most aren’t particularly engaged or motivated by the content.

Edupreneurial Expertise-Based Businesses

The last group is what we term expertise-based businesses—consultants, coaches, speakers, authors, and other experts who generally operate solo or as very small businesses. For this group, courses, membership sites, events (online and off), and other types of learning experiences have become a primary path for moving beyond the traditional “time for money” approach of charging hourly or project fees. Evolving from expert to edupreneur offers the possibility of creating a more predictable, sustainable, and potentially sellable business.

Advances in technology have been particularly important for this group. The emergence of relatively low-cost software-as-a-service (SaaS) tools and platforms for creating and selling digital learning experiences has made it possible for a single individual with little to no budget to produce, sell, distribute, and support offerings that just a couple of decades ago would have required a team of people and tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The result is that publishing a course has become what publishing a book became in the aftermath of self-publishing platforms. You’d be hard pressed to find an established coach or consultant who hasn’t published a course or who doesn’t have plans to soon. Many provide courses and/or community within the context of membership or subscription sites, and educational Webinars are the coin of the realm for lead generation.

As with the commercial providers, the quantity of offerings flowing from this group has contributed to overall commodification and downward price pressure in the market for adult learning. And, as might be expected, quality is all over the map—even more so than with the previous three groups. Low-cost, easy-to-use tools don’t translate into high-quality learning experiences if the people using them have no real background in adult learning or instructional design, and most of the people in this group do not. They are experienced subject matter experts and often excellent marketers, but, aside from the naturally gifted, most are mediocre teachers and facilitators of learning.

Other Providers and Players

The four groups already covered are the ones most focused on producing adult learning experiences that generate revenue directly. As such, they are the main drivers for adult learning as a market. But that doesn’t mean they are only ones impacting the market.

While they do not tend to be revenue centers, and their focus is primarily on advancing the goals of the companies they serve, corporate L&D departments play a significant role in adult lifelong learning. The research in learning science and similar areas that informs the activities of these departments as well as their actual practices very often influence what academic, association, commercial, and edupreneurial providers of learning experiences do. Moreover, from contracting for seminars to licensing e-learning content to sending their employees to conferences, corporations are important customers for the output of the four main provider groups.

Beyond formal learning and development, corporations are also a major source of events for their customers and partners. While these are often oriented more toward public relations and marketing, they are also a source of both formal and informal learning. For example, an event like Dreamforce, hosted by the customer relationship management (CRM) software giant Salesforce, reaches tens if not hundreds of thousands of people annually with a long list of formal educational sessions and informal peer learning opportunities. Smaller versions of this sort of event occur daily throughout the world.

Content marketers—including those who operate on behalf of the lifelong learning providers already discussed—also play an important role. While direct revenue generation is generally not a goal of content marketing, it may be used to funnel people toward paid learning experiences. It can also impact the market by steering people away from paid learning experiences. In many instances, prospective learners may find educational content that is created for the purpose of generating traffic, affiliate clicks, or lead acquisition to be sufficient for whatever learning goal they’re pursuing. Just ask anyone working for the four major revenue-focused providers about the challenge that the plethora of free educational content represents.

Finally, governmental bodies play a role, one that varies significantly from country to country and region to region. In general, investment by governments in adult lifelong learning is relatively minimal in comparison to the amounts that flow into K-12 and higher education. In the United States, for example, Pro Publica reported this in December 2022:

The federal government provided about $675 million to states for adult education last year, a figure that has been stagnant for more than two decades, when adjusted for inflation. And while states are also required to contribute a minimum amount, ProPublica found large gaps in what they spend. Lower funding leads to smaller programs with less reach: Less than 3% of eligible adults receive services.

By comparison, funding from all sources for K-12 education in 2021 was around $795 billion, with $85 billion coming from the federal government. That same year, the U.S. spent about $875 billion on its military.

As noted in a Leading Learning Podcast episode on the topic of defining “lifelong learning,” the situation in Europe and other parts of the world seems to be better, if not necessarily from a funding standpoint, then at least from the standpoint of fuller appreciation for the role adult learning and education play in developing individuals into responsible, capable citizens and thereby bolstering the long-term viability of social institutions and society more broadly.

Given the increasing recognition of lifelong learning as (to quote The Economist again) an “economic imperative,” it seems likely that governments will become more involved in lifelong learning and the market for it over time, whether through increased funding, oversight and regulation, or other paths.

The Future of the Adult Learning Market

One clear lesson to be drawn from even a high-level analysis of the market for adult learning is that it is currently quite siloed and fragmented. Partly because of the issue with definitions, there is no cohesive understanding of “adult lifelong learning” in the way that there is for K-12 and higher education. For efforts to serve adult learners to achieve the impact they could and should, we need a cohesive understanding.

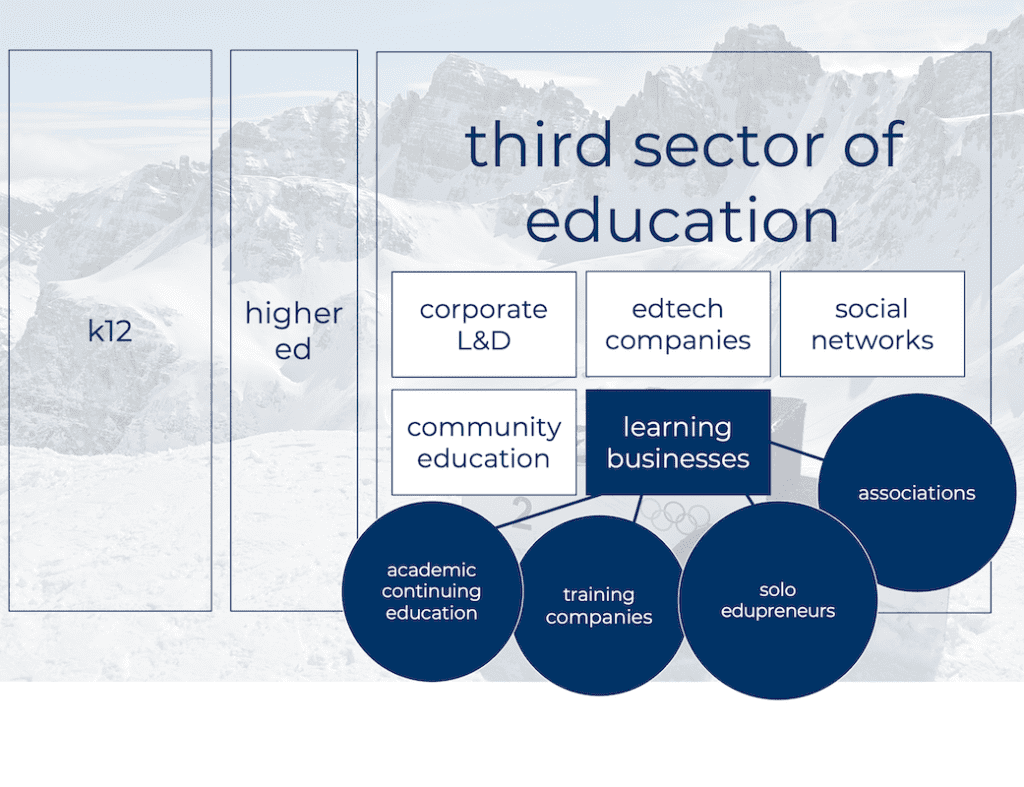

In our work, we’ve moved toward describing the more formal aspects of the adult learning landscape—those served by the four major types of providers—as the third sector of education. While more limited than the full lifelong learning landscape, it has the advantage of being more readily definable and more measurable.

Regardless of whether the phrase “the third sector of education” sticks, if we are serious about cultivating lifelong learning as a public and social good, there needs to be much more dialogue and collaboration across the four major provider groups as well as with corporate and governmental bodies with a stake in learning.

To a certain extent, such dialogue and collaboration already exist. The major MOOC providers, for example, have largely built their brands off the brands of the universities that have provided much of the course content; university PCO departments quite often develop programming meant to serve specific corporate and/or workforce development needs on a local or regional basis; and a growing number of associations have worked to get their certifications embedded into university programs.

Nonetheless, efforts like these remain isolated. There is no larger, connecting vision or shared understanding among the providers that they are participating in a common effort and opportunity. What might spark a change in this situation is unclear, but artificial intelligence seems a strong candidate.

The disruption that AI is likely to create in how learning happens, the financial resources needed to deploy it effectively, and the challenges it will create for learners attempting to navigate the new learning landscape may, at a minimum, lead to greater government involvement, but it also has the potential to prompt more dialogue among the providers as they seek ways to capitalize on emerging opportunities. One catalyst for this dialogue could be greater collaboration among the organizations to which many of the important players tend to belong. As I’ve suggested before, it doesn’t seem like a pipedream at this point to imagine a strong working alliance among some of the major institutions that serve and/or have a major stake in the success of adult learners. Meaningful collaboration among, for example, the American Society of Association Executives (ASAE), the Association for Talent Development (ATD), the Conference Board, and the American Association for Adult and Continuing Education (AAACE), could produce a strong vision for the direction adult learning needs to take and a coordinated plan for supporting the vision.

Whether such an alliance ever happens or not, the market for adult learning will continue to grow substantially for the foreseeable future. The nature of our current world demands lifelong learning, and adults and their employers are clearly willing to pay for it.

The market has grown increasingly sophisticated over the past decades as technology and approaches to learning have evolved, and the emergence of AI practically guarantees that it will become even more sophisticated. It seems inevitable that more personalized and social, informal learning experiences will gain ground as they become easier to deliver, track, and (given that this is, after all, a market) monetize. These types of learning experiences tend to be more attractive to learners and, by and large, are much more effective than traditional lecture-based approaches.

As more informal and personalized approaches to lifelong learning take hold, it will become much clearer that the definitions currently applied to the market are far too limited. The revenue potential is likely many, many multiples of what current analyst reports tend to suggest. At the same time, the revenue potential is arguably the least important aspect of this market.

The value of lifelong learning in enabling individual human beings to thrive and in enabling humanity, collectively, to overcome the daunting challenges we currently face is inestimable. In that sense, in every sense, lifelong learning truly is imperative.

Need Help Reaching Your Market?

At Tagoras, the parent company of Leading Learning, we are experts in the global market for continuing education, professional development, and lifelong learning. For more than two decades, we have helped a wide range of organizations increase the reach, revenue, and impact of their educational offerings.

Awakening Organizational Culture with Catherine Bell

Awakening Organizational Culture with Catherine Bell

Leave a Reply